Are You Thinking Like an Artist?

Confessions of a creative mercenary.

By Lon Shapiro (originally published on Medium, September 5, 2019)

If you make a living as a creative, are you an artist or a sell-out?

Da Vinci had rich jerks for clients who asked him to do their portraits, murals, and even sets and costumes. He wrote that “Art is never finished. Only abandoned.” Sounds pretty unsatisfying.

On the other extreme, Van Gogh was ignored by art critics until after he died.

Art Nouveau

Alphonse Mucha, one of the originators of Art Nouveau, is best known for posters he created as cigarette, chocolate and biscuit company ads.

Here’s one of his most famous works, a poster for Sarah Bernhardt in 1895.

Regardless of what you think of each style of art, the artists did what they did to make a living, regardless of whether their works became valuable in their lifetime, or whether critics thought their work had any artistic merit.

What is the definition of selling out?

According to Wikipedia, the concept of “selling out” starting with 1970’s punk bands believing their music should be completely independent of commercial influences. The term did not exist before then.

I would argue that this concept is a quaint artifact of our modern privileged lives.

Real artists don’t plan out or worry about their art, they just create.

And whatever they do to make a living — whether it’s waiting tables or designing posters for a concert — is their price to create art. Even if it means the artist turns herself into a commodity. Artists have no problem doing “soul-sucking” work because that’s part of paying your dues.

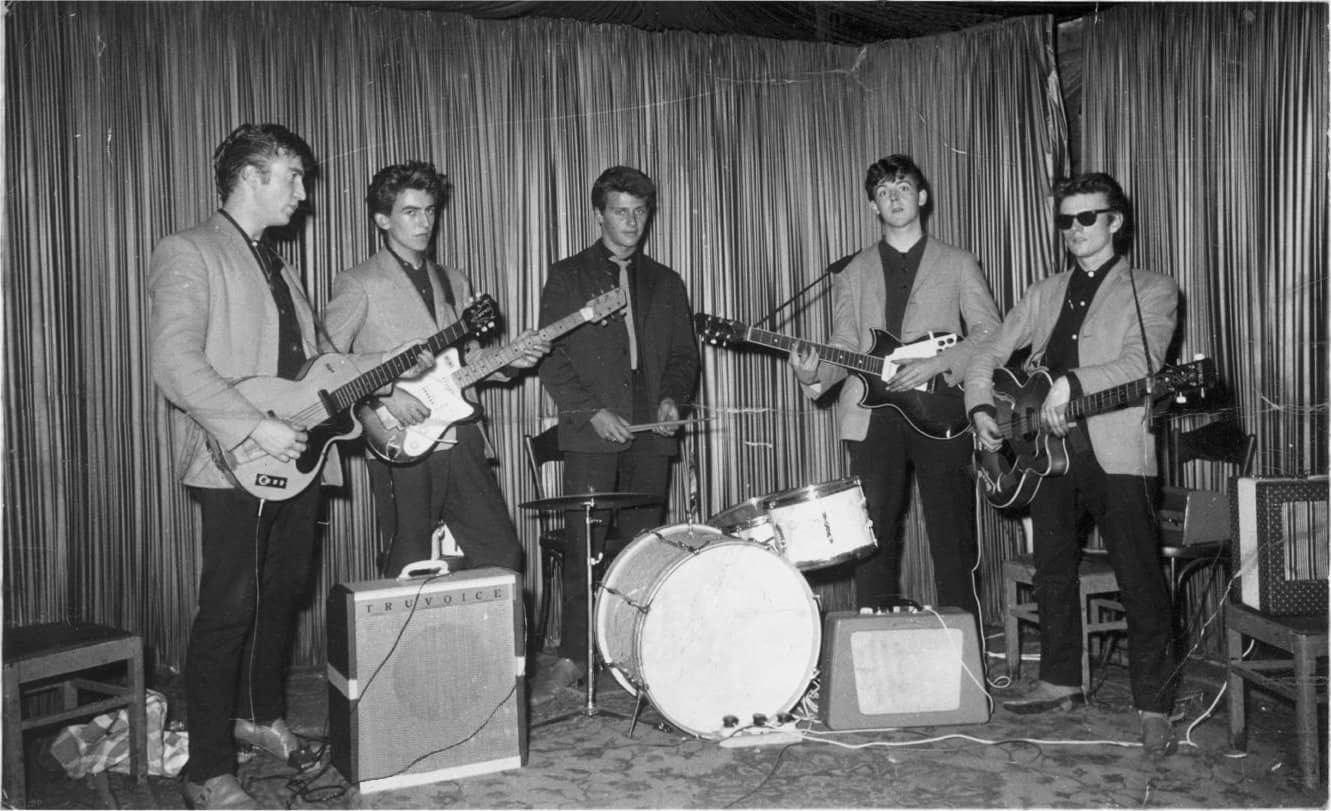

Artists do anything they can to get the chance to create. Posers refuse to take a terrible gig that’s “below them” because they think it won’t help their art. The Beatles started out doing covers of American R&B and Country Western songs and playing gigs in Hamburg in the worst conditions possible, bathing in urinals, and sharing bunk beds in a freezing storeroom with concrete walls and nothing else.

But they honed their skills to become professional musicians and entertainers.

Combining their prodigious skills with the right team of promoters and the genius of producer/arranger George Martin, the boys from Liverpool revolutionized pop music. Within four years, they invented almost every genre of rock music we listen to today. But as John said, “we were just a band that made it very, very big, that’s all.”

“We were just a band that made it very, very big, that’s all.” — John Lennon

The Beatles didn’t think of themselves any differently than other people. They just wanted to make a living at the beginning.

They were regarded as a pop fad by serious music critics in those early years.

By the time the band broke up, universities offered classes to analyze their musical contributions to the 20th century.

I don’t believe that selling out is a problem any of us will ever have to worry about. Unless, of course, you’re Adam Sandler and you’ve got a movie deal with Netflix. Very few of us will ever be forced to accept a ton of money to produce three more novels or albums than we have left inside us.

It’s a little presumptuous to even talk about being “true to your art” since no one will know whether it’s art or kitsch or demented rantings until people are picking through your work at some point in the distant future.

I’m a creative mercenary

As someone who has been paid to write and produce commercials, develop web sites, and create the branding for everything from theme park rides to organic food to paint, I don’t claim to be a real artist.

But who’s to say that two hundred years from now, art critics aren’t going to say some of my best work was a good example of post-post-modern snarkism, or self-aware meta-expressionism or some other snooty classification?

Just like my Art-Nouveau buddy with the coffee and biscuit ad posters.

To reach a professional level in anything, there are necessary compromises that facilitate further growth.

Being a professional in some creative capacity is always going to be a form of collaboration, whether it is between you and a client directly or between you, others in your company and a client.

I learned long ago to let go of my ego because there are always good ideas coming from other people within this collaboration.

(Though they may be few and far between, it’s worth it to wade through all the crap to find that one gem that takes your work to a completely new level.)

Sometimes we don’t go with the best concept because clients can be idiots.

But the creative exploration — the grind on behalf of clients to come up with five, ten, even twenty concepts — is a necessary process that assures me that we came as close as possible to finding the right solution.

Is having absolute freedom even helpful for you to blossom as an artist?

That’s something to consider as you begin your career.

During the renaissance, the rules were simpler. You knew when you were trained as an apprentice and then earned the title of journeyman. If you were super talented and driven, eventually you might become a master.

Today, someone with a smartphone can buy a couple of apps, and think about their destiny as an “artist.”

I used to work for an award-winning illustrator/designer at his studio.

Students from his alma mater would come to show him portfolios that might contain a CD cover they designed over the course of a semester.

We used to churn out an entire CD package in a day, and that reminds me of a quote by a guy who definitely could “think different.”

“Real artists ship.” ― Steve Jobs

It may take years to become technically and creatively proficient enough in your craft before you should think about your “art.”

One famous designer (his name slipped my mind for the moment) said that having parameters and client-mandated limitations improves the creative process.

Think about getting your chops down so you can create art at a professional level.

Young people rarely understand the process of becoming an artist, but hindsight is 20–20.

What seems like a century ago, I was a young aspiring professional tennis player. I didn’t want to hurt my “art” by taking anything away from the focus of my training, like giving lessons, or networking with rich alumni. In hindsight, I failed to learn key lessons that would have helped me become successful — lessons I learned years later after teaching for a living.

On the flip side, one of my contemporaries worked as a bricklayer for an entire year to save up the money so he could travel the circuit.

He eventually won a Grand Slam title.

Artists throughout the ages have dealt with all kinds of difficulties, and it is the combination of life experiences and pain that fuels the real creative passion expressed in great work. So I’m not sure young artists of any kind should be worried about “soul-sucking” work, even if that means working as a bricklayer.

Artists have soul, but how do you know you’ve even got one?

When you’re young (in the sense of life experience — a 14-year-old victim of abuse or battlefield survivor has suffered more than a 35-year-old white guy who lived his entire life in a town with no black people), you haven’t even scraped the surface to find out what you’re made of.

Maybe it’s the drudgery of years of soul-sucking work that is required to get connected with your soul.

Even if you have a full time job, there is always time for creating art.

These are the most creative periods during my day: waking up from a dream; hiking through the hills with my dogs*; taking a dump (don’t laugh, that was the seat of choice for the author of the Protestant revolution); being forced to do gardening; driving; reading; talking to my family; seeing or listening to something inspirational; thinking of problems right before I go to sleep; and occasionally, during work.

The creative process means paying attention to everything around you and being open to any idea, no matter how ridiculous it might seem.

Coming up with ideas can be an almost non-stop process, regardless of what you are doing at the time.

The only time my creativity gets shut down is when I am forced to do something truly soul-sucking: watching an episode of Friends, or listening to drunken friends babble about trivial daily activities with an attention to detail that would make a Swiss watchmaker jealous, and drive a court reporter to the brink of madness.

To be an artist, my final piece of advice is to empty yourself.

Get rid of all the superficial diversions in your life — social media, you tube videos, Tinder, bars, chi-chi restaurants, and anything that can be considered addictive and self-medicating.

You might also need to distance yourself from negative influences that include friends or family.

The process to becoming an artist isn’t that different from creating art. Consider the words of one of the all-time greats:

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” — Michelangelo.

When you can experience nothingness, you’ve taken the first step toward finding the artist inside you.

It will be boring at first.

It may become painful when you’re no longer distracted from facing your personal demons. You might feel like you’re going crazy.

Good.

If you can’t see your own craziness and the absurdity of this world, that’s when you should be worried.

Eventually, you will see if there’s something inside you that needs to be expressed for you to feel alive.

It’s that passion that will turn you into an artist, and nothing else.

And once you find it, you might find that you can express it anywhere, regardless of whether you’re playing guitar in a subway station, spray painting graffiti on an abandoned warehouse, or writing a best-selling novel.

The ability to live totally in the present, regardless of the activity, is what connects you with your creativity.

All the worrying, introspection and self-obsession with money, popularity, self-esteem, and personal branding is the real sell-out.

Cover image photo by melissa mjoen on Unsplash